By Anne Menzel

In July 2016, I began to prepare for my first return to Sierra Leone since the 2014-15 West Africa Ebola outbreak. My last stay had ended shortly before the first Ebola cases were officially registered, and my return was to begin in early November 2016. Its purpose was to conduct three months of archival and field research for a project titled Redressing Sexual Violence in Truth Commissions. The Labelling of Women as Victims and its Social Repercussions. One aspect to be covered by my research was the current state of fighting sexual violence against women and girls in Sierra Leone. Pertinent questions were: who is doing or funding which kinds of measures based on which policy-narratives, and (how) do these measures and narratives reflect local experiences, needs, struggles and aspirations? Among current reconstruction efforts after Ebola, I expected to meet a fair number of activities around sexual violence against women and girls.

My expectations were based on recent reports and on experiences in the aid industry: During and in the immediate aftermath of the epidemic, there had been press and NGO reports about increases in sexual violence and teenage pregnancy. Both were attributed to the closing of schools (a quarantine measure) and escalating economic hardship.[1] Girls were at home or in the streets rather than in school, while food prices were rising and while it was becoming even harder than usual to earn a living or survival. It was judged plausible that these conditions had rendered women and especially young girls even more vulnerable to sexual abuse. According to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) factsheet, there were coordinated plans to allocate USD 2 million to the fight against sexual violence from June 2015 until December 2016 ‒ as part of the Ebola recovery efforts.[2] I presumed that this was only the tip of the iceberg.

Also, I had already experienced that sexual violence was regarded as a relevant and actionable problem to be addressed in the context of post-Ebola reconstruction efforts. In May 2015, when Ebola cases had markedly decreased and organisations were rushing in to plan and pitch reconstruction projects, I was approached by an international NGO looking for a consultant to conduct a needs assessment among vulnerable populations (women, children and youth) in the capital city Freetown and some rural areas. Based on this assessment, the prospective consultant was also expected to come up with a project proposal. There had recently been an EU call for relief and reconstruction projects for Ebola-hit West African countries and the NGO was looking for relevant and actionable ideas that would match the call as well as its own established specializations and competencies. The country director clearly communicated her preference for a needs assessment result that would enable a project centred on Ebola-related sexual violence. During my skype job interview she told me,

Please don’t come up with something like ‘people are hungry and people are sick’. Everybody knows that, and there is nothing we can do about it. We need something more specific to get these EU grants. Maybe something like Ebola and sexual violence.[3]

I ended up not taking the job, but it still made a lasting impression on me. Over the following months (until July 2016) I did not have time to systematically follow up on current policy-developments in Sierra Leone. But I assumed that sexual violence against women and girls was a topic that donors and their implementing partners (international and national/local NGOs) were eager to address.

A post-Ebola diversion?

It did not take me long to begin to doubt my expectations. In fact, they did not even last until I left for Sierra Leone in early November 2016. Already in late August, I came across press reports that told a very different story. According to a BBC report, it had actually become more difficult to raise money to assist women and girls who had suffered sexual violence in Sierra Leone.[4] The report specifically focused on the Rainbo Initiative, a national organization, and Familiy Support Units (FSUs), which are part of the Sierra Leone Police structure. Rainbo Initiative runs three Rainbo Centres, one in the capital city Freetown and one, respectively, in two district headquarter towns, Kenema and Koidu. The centres offer a medical examination and counselling to survivors of sexual violence and, if possible, collect evidence for future criminal prosecutions of perpetrators.[5] They are also meant to closely work with FSUs. These are units within the national police structure that were specifically established to respond to domestic abuse (sexual or other) of women and children. Most importantly, they are supposed to make sure that allegations are properly investigated so that cases of abuse can be tried in court – instead of hidden away or settled within or between families according to customary law.[6] Both organizations had originally been established in the context of British-led security sector reforms during and after the 1991-2002 war in Sierra Leone.[7] And both were about to run out of funds and desperately looking for donors willing to step in. The Sierra Leone government had already declined their requests.[8]

Another press report about a post-Ebola lack of funds in the fight against sexual violence drew on interviews with the executive directors of Rainbo Initiative and AdvocAid. The latter is a Sierra Leonean NGO, which offers legal aid to women in Sierra Leone’s over-crowded prisons. The executive directors of both organizations agreed in their diagnoses: funding was going elsewhere. AdvocAid’s executive director, Simitie Lavaly, also provided an explanation, “[D]onors have diverted their priority from human rights funding to the health sector, since its weakness was hugely exposed by the Ebola outbreak.”[9]

Donor fatigue

But I soon began to doubt the idea of a ‘post-Ebola diversion’ as well. When I spoke with AdvocAid’s Simitie Lavaly in November 2016, she actually confirmed these doubts. She explained that AdvocAid had always found it comparatively difficult to attract donors, because the women they assisted were criminal offenders (though many are also imprisoned for non-criminal offenses, such as failure to repay loans) – and major donors preferred victim-centred projects. However, while AdvocAid was getting better at presenting their beneficiaries’ vulnerable aspects (the stories behind the stories that led them to end up in prison)[10] and while Ebola had indeed brought some new policy priorities and funding difficulties, they also had to deal with a more profound donor fatigue. This affected the FSUs and Rainbo Centres even more than AdvocAid. Donors had reached the point at which they really wanted the government to take over funding responsibilities for certain organizations in the area of responding to sexual violence against women and girls,

‘Donors feel that they have poured so much money in the justice system, but they just don’t see the results. So they say, let’s stop the funding, let the government take responsibility. And, of course, this is their right and it makes sense in terms of sustainability. But it also creates a gap.’[11]

FSUs have been chronically underfunded for years and Rainbo Centres can still only offer a very limited set of services in a few location. This has meant that sexual violence cases still rarely make it to court and that survivors do not receive necessary medical attention.[12] Common complaints are, for example, that FSUs have none of the necessary basic equipment, like cars, fuel, pens and paper, to engage in a criminal investigation. Unpaid and insufficient salaries are also a constant problem, as they cause petty corruption. Survivors and/or their families and friends are usually asked for financial contributions before they can even make a report. An elderly woman in Freetown (a petty trader surviving on a hand-to-mouth basis) recently told me this typical story,

One time, I went with a girl [to the local FSU]. Three men had beaten and abused her. We went to the hospital and they gave her a medical paper. Next, we went to the police and sat down with one police woman. This woman told us to bribe her. She wanted 20.000 [Leones, roughly 3 Euro) before ever she was ready to do something. I told her that I was only holding 10.000. She said that she would wait first. And that was it. We did not go there again.[13]

During an interview with leading officers at an FSU Freetown in early 2014 (before Ebola), I was told that it was only during the time of the British-led post-war security sector reforms that there was sufficient funding.[14]

While FSUs have been experiencing this ‘gap’ for a number of years now, donors’ retreat from the Rainbo Centres is more recent but still predates Ebola. In my first Rainbo interview with a member of the board of governors of Rainbo Initiative, she explained that the organization had been in a difficult process of transition since 2014.[15] Here is her account of the organization’s history in brief: She explained that the very idea to found Rainbo Centres had come from a British policeman, Bill Roberts, who was a consultant for the British-led security sector reforms in the early 2000s.[16] Because of his initiative, Rainbo Centres became modelled after an organization in Manchester (most likely St. Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre).[17] The idea was to establish more private and secure-feeling places outside the police stations where women and girls would receive care and counselling and, at the same time, where professionals would be able to collect physical evidence of abuse. The three Rainbo Centres were established in 2003 (Freetown), 2004 (Kenema) and 2005 (Koidu). Until 2014, they were fully managed by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), an international NGO. This meant that IRC raised funds and managed the centres’ budgets. From 2014 on, however, IRC supported Rainbo to become independent – under a national organization called Rainbo Initiative. This process was also approved and supported by Rainbo’s most important donor, Irish Aid, the Irish government’s programme for overseas development. Irish Aid has a steady relationship with IRC, which is its implementing partner in Sierra Leone. This relationship continues[18] while Irish Aid has been seeking to phase out its support for Rainbo Centres.

The idea was that an independent Rainbo Initiative would be able to raise and manage its own funds.[19] But without an international partner and the accompanying donor-connections, Rainbo Initiative has been unable to attract new donors. As an emergency measure, it received one last grant from Irish Aid to cover nurses’ and counsellors’ salaries until the end of January 2017; an additional grant from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) to cover medical supplies, stationery, food etc. did not come through.[20] When I visited the centre in Kono in February 2017, it was still operating and patients were coming in every day. The staff told me that they remained hopeful and trusted that their new executive director − James Fofanah, who had just started the job in January 2017 − would soon find a donor for them.[21]

Moving on to teenage pregnancy

When I spoke to Mr. Fofanah in late February 2017, he was indeed in the process of preparing several grant proposals. He explained that, at the moment, he really just wanted to make sure that the centres survived. In the medium and long term, however, he was going for a different strategy. He argued that it was absolutely necessary to include medical care for survivors of sexual violence into the regular government budget as part of the ‘free health care package’. The existing package is only for pregnant women, breast feeding mothers and infants under the age of five (and even their ‘free’ treatments are often not actually free of charge; petty corruption has been a major obstacle hindering access to basic health care in Sierra Leone[22]). What this means in practice is that survivors of sexual violence officially have to pay for themselves if they want to receive medical care − aside from an initial free check-up at Rainbo Centres (if there is a centre nearby) and unless they fall into the categories of pregnant women, breast feeding mothers and infants under the age of five. Mr. Fofanah argued that this situation urgently needed to change. In this, he is in perfect agreement with donors such as Irish Aid who have been advocating for the inclusion of sexual violence survivor-care into the government’s ‘free health care package’.[23]

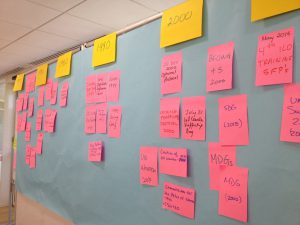

In addition, Mr. Fofanah was also hoping to be able to persuade donors to include Rainbo Centres into the new focus on teenage pregnancy. This focus had been pushed during Ebola when sexual abuse and teenage pregnancies were reported to be massively on the rise due to girls’ increased vulnerability. Still, the topic was not exactly brand new. It had been introduced to Sierra Leonean policy makers via a widely received United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report in 2010[24] and had already been designated as a priority area for coordinated donor and government action before Ebola.[25] After Ebola, there are certainly no signs that it is slowing down. To the contrary, as I was speaking with Mr Fofanah in late February 2017, Irish Aid and IRC had just launched a new project in Kenema and Kailahun and additional teenage pregnancy related activities were going on in partnership with the international NGO Save the Children and the United Nations Populations Fund.[26] All these current activities focus, in one way or another, on raising awareness for the problem of ‘teenage pregnancy’ − as sexual abuse, as a considerable health risk and as a barrier to education and empowerment – and on encouraging girls to ‘say no to early sex‘ and stay in school.

Mr Fofanah felt that Rainbo Centres could complement these efforts. He referred to a recently published independent policy analysis, which takes a critical stance on the emphasis placed on changing girls’ attitudes and behaviours and calls for an approach that also considers changing contexts and structures.[27] This was where Mr. Fofanah saw a potential role for Rainbo Centres that might still attract donor-funding – if and when donors were ready to again invest in a less individualized approach to social change.

Lessons learned

What is there to be learned from this glimpse into the world of donor-involvement in the current ‘sexual violence situation’ in Sierra Leone? It is clear that donors have certainly not lost interest. Instead, they have shifted their focus towards new priorities offering problems that may still be solved and towards areas where donor-funded projects may still make a measurable impact and generate ‘value for money’[28]. It appears that such impact no longer seems possible with FSUs and Rainbo Centres. They should long have become owned by the national government or, at least, they should have become independent of steady donors who are no longer willing to take over government responsibilities.

The current situation in Sierra Leone appears to confirm perspectives that interpret donor-funded activities in the name of aid, peacebuilding and development as self-referential. In practice, they are about designing and doing ‘good projects’ that can have a demonstrable impact according to predefined indicators and standards. This happens, ’relatively independently of beneficiaries’ needs and preferences.’[29] For example, it might well be that many Sierra Leoneans would prefer external donors to make good use of available money to fund basic services − even if donors consider this a government responsibility and regard such actions as unsustainable and prolonging dependency. But, in any case, this option is never on the table. Donors decide when it is appropriate to push certain topics and withdraw funding in other areas – all in the name of assisting/empowering vulnerable people while respecting the state’s sovereignty (and avoiding accusations of neo-colonialism). When desired impact seems no longer possible, it becomes plausible and even inevitable to move on to problems that are more ‘attractive’, in the sense that they can be perceived of and presented as actionable and rewarding. This appears to be the case for ‘teenage pregnancy’ in Sierra Leone, which has been made into a matter of changing harmful attitudes among teenage girls and encouraging them to focus on their education and socio-economic empowerment. In addition, it is also presented as an issue of sexual violence − only without the messy components of Sierra Leone’s post-war security structure that have turned out as such disappointments.

It is still uncertain where this situation is headed and whether critical voices regarding the current individualized approach to social change in the realm of ‘teenage pregnancy’ will be heard. Much will probably depend on Sierra Leone’s 2018 general elections and on a new governments’ willingness and ability to make credible commitments to effectively become responsible for old problems and new priorities.

[1] See, e.g., Nina Devries, ‘Ebola drives increase in sexual violence in Sierra Leone, experts say’, Al Jazeera America, 20 February 2015, http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/2/20/sex-assault-on-the-rise-in-sierra-leone.html (last accessed 19 April 2017); Sheik Alie Y. Kallay, ‘Ebola and Gender Violence in Sierra Leone’, Awareness Times, 16 March 2015, http://news.sl/drwebsite/exec/view.cgi?archive=11&num=27323 (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[2] See UNDP, ‘Ebola Recovery in Sierra Leone: Tackling the rise in sexual and gender based violence and teenage pregnancy during the Ebola crisis’,

http://www.undp.org/content/dam/sierraleone/docs/Ebola%20Docs./SL%20FS%20SGBV.pdf (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[3] Skype job interview, 20 May 2015.

[4] Umaru Fofana, ‘Sierra Leone: “Real men don’t sleep with school girls”’, BBC Focus on Africa, 25 July 2016, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p042kh69?ocid=socialflow_twitter (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[5] See Lina Abirafeh, ‘Building capacity in Sierra Leone’, Forced Migration Review 28 (2007), p. 20.

[6] See Lisa Denney and Aisha Fofana Ibrahim, ‘Violence against women in Sierra Leone: how women seek redress’ (Overseas Development Institute, London 2012), p. 13.

[7] See Peter Albrecht and Paul Jackson, ‘Security system transformation in Sierra Leone, 1997-2007’ (Global Facilitation Network for Security Sector reform and International Alert, Birmingham and London, 2009).

[8] Umaru Fofana, ‘Sierra Leone: “Real men don’t sleep with school girls”’, BBC Focus on Africa, 25 July 2016, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p042kh69?ocid=socialflow_twitter (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[9] Mustapha Dumbuya, ‘Funding issues threaten support for Sierra Leone’s sexual abuse victims’, News Deeply, 23 August 2016, https://www.newsdeeply.com/womenandgirls/articles/2016/08/23/funding-issues-threaten-support-for-sierra-leones-sexual-abuse-victims (last accessed 19 April 2019).

[10] See, e.g., ‘Favour’s story’, http://advocaidsl.org/project/our-stories/favours-story/ (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[11] Interview in Freetown, 14 November 2016.

[12] For an overview, see Lisa Denney and Aisha Fofana Ibrahim, ‘Violence against women in Sierra Leone: how women seek redress’ (Overseas Development Institute, London, 2012).

[13] Informal conversation in Freetown, 10 December 2016.

[14] Interview in Freetown, 10 January 2014.

[15] Interview in Freetown, 24 November 2016.

[16] See also Peter Albrecht and Paul Jackson, ‘Security system transformation in Sierra Leone, 1997-2007’ (Global Facilitation Network for Security Sector reform and International Alert, Birmingham and London, 2009), p. 40.

[17] Rainbo Centres were originally called ‘Sexual Assault Referral Centres’. On the centre in Manchester, see http://www.stmaryscentre.org/ (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[18] See Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Ministers Flanagan and McHugh announce €2.2 million in funding to the International Rescue Committee’, press release, 23 February 2017, https://www.dfa.ie/news-and-media/press-releases/press-release-archive/2017/february/ministers-announce-funding-to-irc/ (last accessed 19 April 2017).

[19] Interview with Irish Aid’s gender advisor, Freetown, 27 January 2017.

[20] Interview with a member of the Rainbo Initiative’s board of governors, Freetown, 24 November 2016.

[21] Interview in Koidu, 6 February 2017.

[22] See Amnesty International, ‘At a crossroads: Sierra Leone’s free health care policy’ (Amnesty International, London, 2011).

[23] This is according to Irish Aid’s gender advisor, interview in Freetown, 27 January 2017.

[24] Emily Coinco, ‘A glimpse into the world of teenage pregnancy’ (UNICEF, New York, 2010).

[25] Government of Sierra Leone, ‘Let girls be girls not mothers: national strategy for the reduction of teenage pregnancy (2013-2015)’ (Government of Sierra Leone, Freetown, 2013).

[26] Interview with Irish Aid’s gender advisor, Freetown, 27 January 2017.

[27] Lisa Denney, Rachel Gordon, Aminata Kamara and Precious Lebby, ‘Change the Context not the girls: improving efforts to reduce teenage pregnancy in Sierra Leone’ (Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium/Overseas Development Institute, Report No 11, London, 2016).

[28] ‘Value for money’ as a principle for programming and project-making is, ‘is about maximising the impact of each pound spent to improve poor people’s lives.’ DFID, ‘DFID’s approach to value for money (VfM)’ (Department for International Development, London, 2011), p. 2.

[29]See, e.g., Monika Krause, The good project: Humanitarian Relief NGOs and the Fragmentations of Reason (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, and London, 2014), p. 4.